Award-winning food writer Karim Ganem Maloof explores the history of the breadfruit, from its colonial roots in Colombia and the Caribbean, to its role in the mutiny on the Bounty, to the taste and versatility that obsessed Marlon Brando.

EDITOR’S NOTE: “The Breadfruit Tree” is from the Colombia issue of Stranger’s Guide. It features insightful stories about this complex country that’s gone from being known as a place of cartels and conflict to a destination near the top of many travel itineraries.

Breadfruit is best if you remove the heart. The heart tends to fill with cholesterol and bitterness because it’s the most porous part of the fruit and greedily absorbs the oil when you fry some slices. In contrast, the rest of the breadfruit is sweet, soft, nutritious. Perhaps it’s the salty air that gives it a balanced flavor, or the volcanic and coralline soil of the San Andrés, Providencia, and Santa Catalina archipelago, 470 miles off the Colombian coast, where it grows everywhere.

Breadfruit tastes best with hunger, but also it goes well with fish. I confess that in certain restaurants I’ve ordered snapper only to get at the side dish. And that’s because a lot of cooks don’t feature carbohydrates in a leading role but only as supporting actors. We islanders cut the oblong fruit in half, peel it, and, after tossing the heart, cut it into crescents that we fry until golden. Colombians from the mainland who visit the island are astonished when they try breadfruit because they don’t know in which branch of the kingdom of fried food to place this tender, crunchy and starchy snack. Since it is hard to eat something without knowing what it is, the tourists resort to comparisons for help: Is it a kind of potato or cassava or taro? they ask. It’s that and other things, one says, nodding, thinking that all these conjectures point to tubers that hide their hearts in the dirt, not to a fruit elevated in the heights of a tree.

One of those trees grows on the patio of my childhood home. It’s now over 30 years old; we’re the same age, but it’s 13 feet taller. Its leaves look like green flames drawn by a child. In the garden next to my parents’ house, a younger tree stretched a couple branches above the fence. Early some mornings, I would watch my mother sneak a small ladder over to the fence, climb up, and reach over for one of the ripe fruits on the young tree when ours didn’t have any that were ready. My dad justified those petty thefts with a botanical judgment: “That tree is a shoot from ours, the child of one of its little tails.” The species of breadfruit that prospers in the islands is a seedless hybrid, so it’s propagated artificially through grafts and cuttings, or naturally, as in this case, through shoots from the roots.

The neighbor’s young tree sprouted from the roots of ours, which expanded until they found new tunnels of light. The archipelago’s ecological authorities say that where there’s one breadfruit, there are at least three more. The damn things are never alone! They’re as gregarious as old gossips. This spontaneous offspring stayed just on the other side of the fence, but some of its branches hung over onto our side. It was just the right distance for a youth to develop under paternal guidance but without the shadow of its progenitor keeping it from breathing.

It’s impossible for a single family to eat the quarter-ton of fruit that a generous tree produces in a year. So, instead of leaving the garden a minefield full of rotten fruit like half-exploded bombs, one pawns off a pair of breadfruits on any visitor who chances by the house. It’s a gift that’s less expensive to give than not. It’s so tiresome to force ourselves to pick up all the fallen fruit, to think in terms of leaving nothing to waste, to feel obliged to make some profit, gathering it to sell it to others. That is, to break our backs “taking advantage of” nature, when we could easily continue to lie back and take advantage of it another day, at our leisure. A lot of islanders with deep roots here, descendants of the fusion of African slaves and English colonizers, look wearily at their trees and let the fruit rot at the base, where the fallen leaves also clump, looking more like a fire now that they have declined into the warm yellows, oranges, and reds of chlorophyll loss.

Breadfruit tastes best with hunger, but also it goes well with fish.

If it falls by itself, breadfruit ripens all at once. As with humans, life’s hard knocks cause it to mature. Therefore, to keep it from rotting, it’s better to use a ladder and remove the fruit from the tree gently. A coddled breadfruit is one that’s at just the right moment for eating. However it’s more common, because of the great height they hang from, to use a long stick to get them down, breaking the stem that joins the fruit to the branch. Then you have to milk it. Tilting the fruit on its side, so that the latex that has remained in the stem, a remnant of the mother’s sap, drains away.

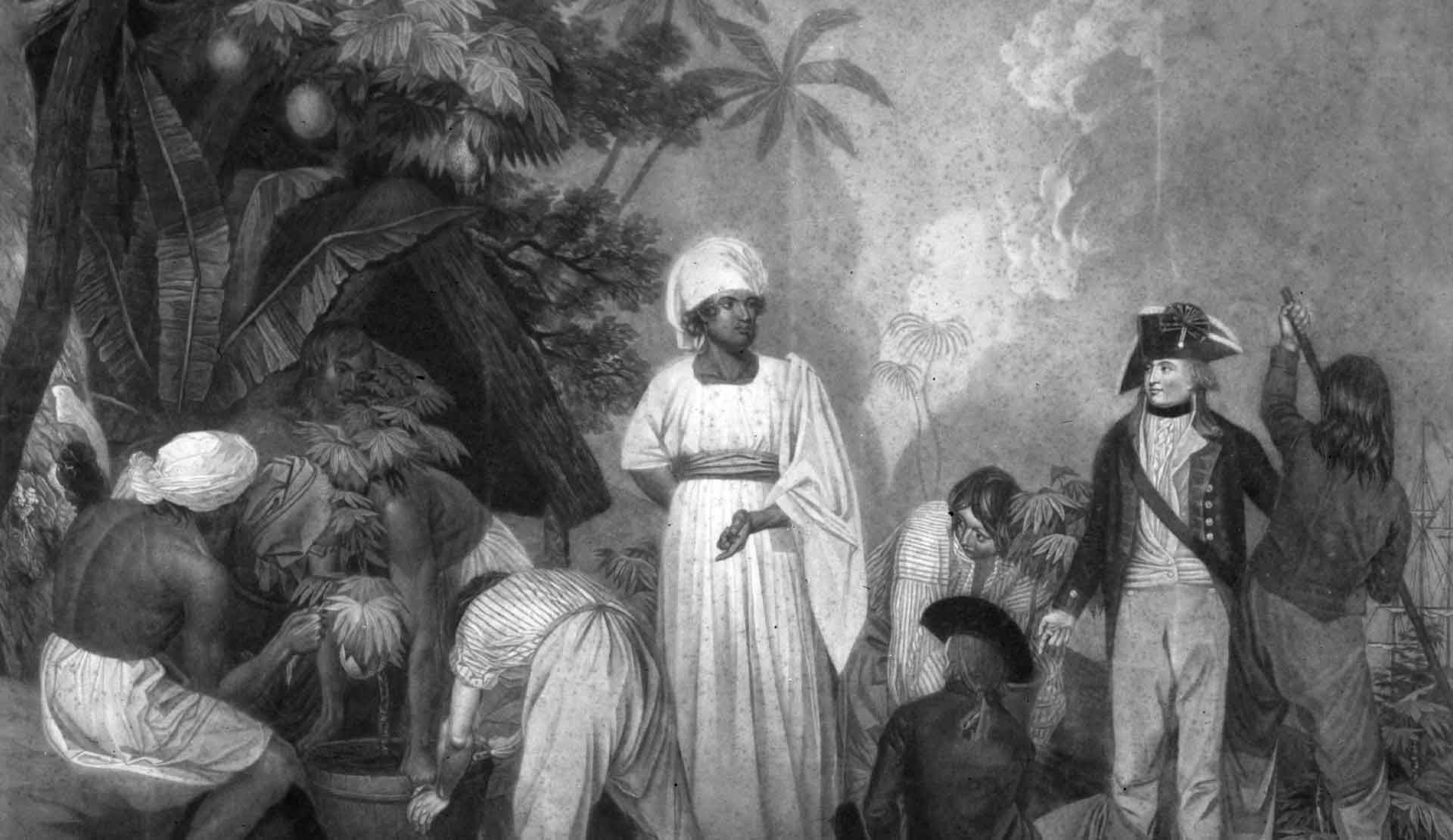

Breadfruit is native to Polynesia. The natives disseminated it on every new island they visited, toting cuttings with them. The English discovered it there and saw in its nutritional value, flavor, and, in particular, low cost, a way to fuel their empire of Caribbean plantations. English Puritans docked on these reefs in the 17th century, laden with specimens of cotton and tobacco, as well as enslaved from West Africa. At the same time, the Spanish had their own robust operation importing enslaved Africans to the Caribbean coast of South America, through the port of Cartagena, to replace the labor of the indigenous population that they had decimated. Slavery abounded in Colombia and throughout the Caribbean islands, bringing profits to different empires, but similar challenges of managing, and feeding, an enslaved work force.

In the late 18th century, Joseph Banks, the botanist and slave-owner who presided over the Royal Society, organized an expedition to Tahiti to bring breadfruit trees to feed, without cost, the slaves of Jamaica and Barbados, as well as small colonies like San Andrés. The HMS Bounty was outfitted to bring breadfruit back from Polynesia: the main cabin, built originally for the captain, was turned into a greenhouse to shelter more than a 1,000 plants; it had glazed windows, skylights, a lead-covered floor, and a drainage system to prevent the waste of fresh water. William Bligh was in charge of the task and sailed with a crew that succeeded in making it to Tahiti and convincing the local headmen to give them hundreds of specimens. After a few months on land, they sailed again. But the memory of the time lived freely in Tahiti’s paradise made the ship’s crowded quarters even more intolerable, a consequence of the scarce free space that that floating greenhouse allowed; to the thirst for love that the native women’s absence provoked was added a more visceral thirst because the lion’s share of fresh water was reserved for the trees.

The sailor Fletcher Christian organized a mutiny. He and his followers threw the plants overboard, together with the captain and the few crew members who remained loyal to him. Fletcher set the men adrift on the high seas in a small boat with limited food and water. His attack would showcase the extraordinary natural qualities of both the breadfruit and Captain Bligh. The trees, tossed into the sea, secured a foothold among the reefs, where they formed a semi-submerged frond. Captain Bligh would later bear witness to this phenomenon: He survived the danger, made his way to London, and went back to Polynesia in pursuit of the mutineers before returning to the Caribbean with the breadfruit specimens.

The mutiny on the Bounty has been a fertile historical episode for fiction. Marlon Brando starred in one of the films based on it, playing the role of Fletcher. During the filming of The Mutiny on the Bounty, in Tahiti, Brando devoured heaps of breadfruit; he ate it with everything and at all hours of day and night. He even had an assistant specifically charged with supplying him with it grilled, fried, boiled, with cheese, as porridge. In contrast to the character he portrayed, the young Brando professed an adoration for the starchy fruit that foreshadowed the roundness that he himself would acquire over the years.

It’s said that enslaved Africans in the Caribbean didn’t much like breadfruit when it first arrived. But the force of habit and the whip guaranteed its consumption, which later evolved into true love. We think that the natives of Polynesia never fried it; that must have been an African idea. Here, breadfruit came to be eaten in a lot of other ways: it was sun-dried to make flour for baking breads and sweets; when the crop was too abundant, it was buried underground to ferment until it acquired a pasty consistency (furo, they call it in Polynesia); and a sugary gruel was made with very ripe fruit. Many years ago it was given the name “criminal porridge” because it was fed to prisoners. They, of course, detested that monotonous diet, and some argued that it was the porridge that was “criminal” because of the deadly drowsiness it causes.

On our island, breadfruit keeps a prudent distance from the sea, at least some 650 feet from the coast, because it doesn’t like too much salt (its heart, like ours, is damaged by excessive sodium). Recently, a devastating hurricane swept through the archipelago, the strongest on record. Meteorologists named it Iota, after the letter in the Greek alphabet. It knocked down the majority of the trees by the shore and left without leaves those that remained standing. My breadfruit weathered the onslaught, but its leaves were burned by the salt and the wind; its edges are now brown and grayish. One of the fruits that we picked up during those days had a withered heart. Iota knocked down the neighboring breadfruit whose fruit my parents used to steal. No one has yet hauled away the trunk that clings to its leaves and exposes, without modesty, unearthed, the snarl of roots at its base. A thick filament, like a human torso, is its last link to the soil. It’s the root it shares with my tree, which won’t let its fallen offspring go.

Recently, I’ve noticed that another pair of shoots have emerged on the other side of the fence. Two juvenile trunks that look like slim teenagers. Their few, enormous leaves rise almost vertically from the upper part, like mohawks. I figure they’re a year old. They’re children of the pandemic, survivors of the hurricane. Breadfruit matures quickly; in a year or two they’ll be yielding fruit. I’ll watch my mother sneak her ladder underneath their branches.

Written by Karim Ganem Maloof, translated by Joel Streicker, courtesy of Stranger’s Guide.

Explore our selection of hotels in Colombia.