We’re constantly looking around for interesting travel stories to fill the pages of the Agenda. Sometimes we hit. Sometimes we miss. And sometimes, we abandon the idea entirely. Why? It’s hard to explain. Easier to show you.

Have you ever heard of a “Code Grandma?” We hadn’t either — until recently, when we came across a shockingly exhaustive Wall Street Journal article that detailed just how much of a problem the scattering of ashes had become at Disney World. The term “Code Grandma,” however unfortunate, is the way one quoted Disney employee referred to the call for a high-powered vacuum cleaner to discretely remove remains from gardens and rides (the Haunted Mansion, somewhat ironically, serving as a favorite distribution ground).

We thought we could spin off of that topic into our own exploration of the relationship between beloved vacation destinations and final resting places. It was already a risky play, and our research wasn’t able to save the idea. Lead after lead turned into story after story of the TSA mishandling urns on the conveyer belt. That wasn’t what we had in mind, and wasn’t something we thought you’d be longing to read. At least that’s what we told ourselves at the time. Little by little we realized that hey, we’re humans, just like you. And if we thought an idea was interesting, you probably would too — or you’d at least want to know why we thought better of pursuing it.

Most of our eccentric story ideas — the ones that sound so inspired in the pitch meetings — tend to go down in flames during the research process. For example, we were curious about the phrase Montezuma’s Revenge. Offensive? Racist? Yes. The idea started out on a short leash, but among our writers, a hope took hold to find the origin of the phrase, to dive deep into the etymology, and to perhaps expose the suspect beginnings of other crass phrases we might take for granted. Unfortunately, this research stalled out upon the discovery of a host of other offensive phrases referring to the same digestive disorder, and little else. According to a difficult-to-verify account from 1942, the trope of stomach problems associated with travel originated with British and American soldiers overseas, then learning to “guard against ‘Teheran tummy’ and ‘Delhi belly.’”

A pivot to write about the mystery of digestive issues in travel led to the somewhat dry conclusion of airplane-induced dehydration and sudden schedule changes that wreak havoc on the G.I. tract. We thought it was best to leave that for more scientifically minded publications.

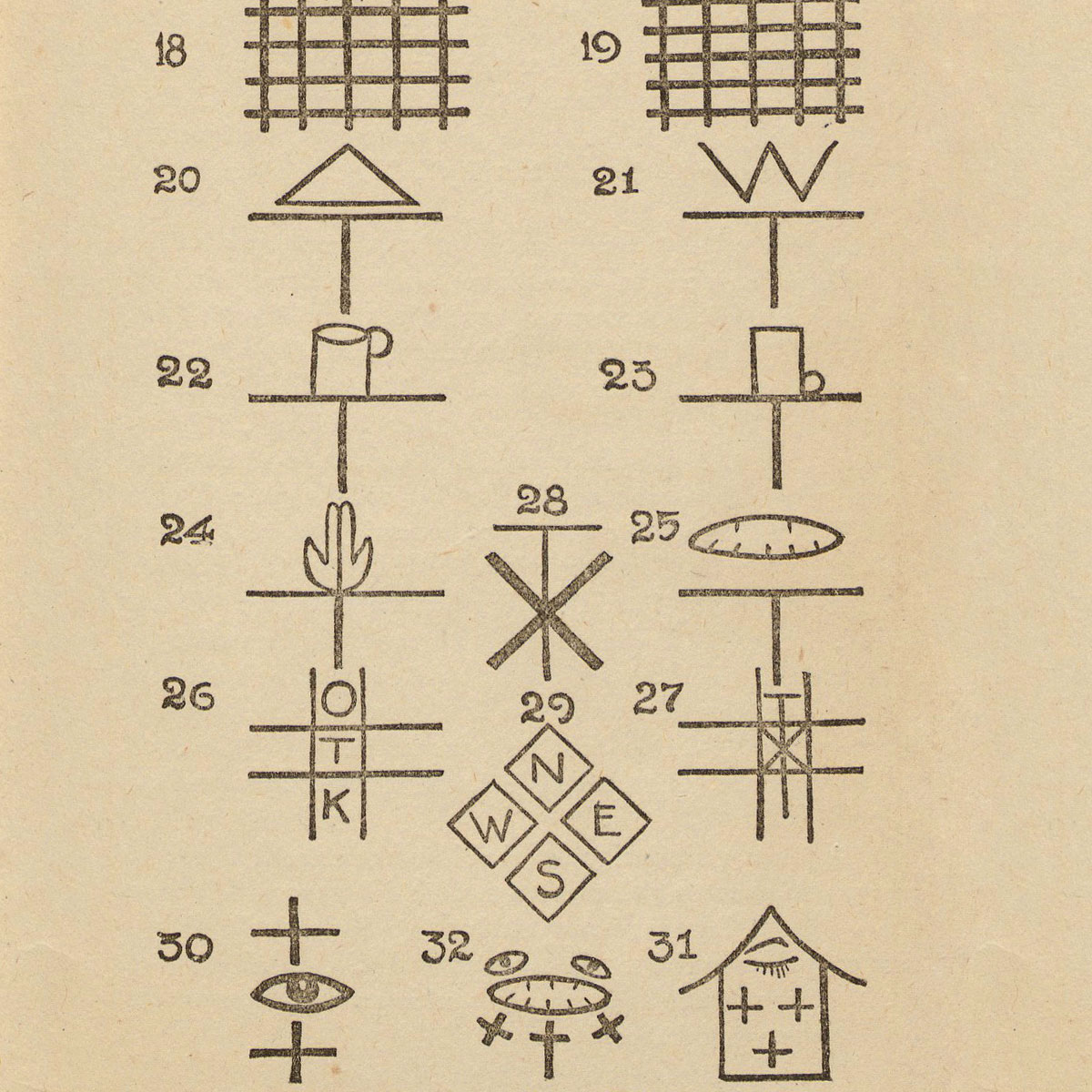

In less bodily spheres of the travel experience, the Mad Men episode “Hobo Code” inspired us, for a moment, to see what we could do with the topic ourselves. Though it’s not the type tourism we typically espouse, the rail-hopping men of the late 19th and early 20th centuries represent another side of travel that is as bold and adventurous as any we usually cover. The idea of the “hobo code” — pictographs drawn in public spaces to convey simple messages to fellow travelers — is fascinating on every level. The simple geometric symbols, which could mean anything from “look out for hoodlums!” to “soliciting allowed on main street,” were meant to make a traveler’s life a little bit easier.

Unfortunately for our article, the experts have some doubts that such a system was really used much in practice. The pros focus instead on the more verifiable “hobo graffiti,” an altogether less glamorous communication system that usually meant a written name, a date, and an arrow in the direction of the traveler’s path. In any event, a cool bit of history. But after we’d done our research, we decided we liked it better in Don Draper’s childhood.

Another factual wrinkle caused us to pause on a celebration of one of our editor’s favorite non-fiction books — Is Paris Burning? — later turned into a star-studded 1966 war epic written by Gore Vidal and Francis Ford Coppola and featuring Orson Welles and Kirk Douglas, among many others. That story is Paris, 1944, after the allies have pushed well into France and Hitler orders the Nazi general in charge of the city to turn Paris into “a pile of rubble.” According to a memoir by that general, Dietrich von Choltitz, his refusal of the order saved the city’s famous landmarks and preserved the Paris that stands today. His heroic version of events is echoed in the book, and later in the movie. A truly amazing story, and for us, a worthy way to highlight one of the world’s most glorious destinations, especially after the 2019 fire at Notre-Dame.

That is, until you read recent counterpoints from some historians, that, when they put it bluntly, say Choltitz’s “version of events is pure fantasy from [a] self-aggrandizing former general” — that he never had the firepower or control to raze the city in the first place. By the time Hitler gave the order, say these credible detractors, Paris was already well in the hands of the resistance. We weren’t sure who to believe, and decided against attempting to litigate the historical truth. In fact, the most lasting legacy of Is Paris Burning? might be how it inspired the title of the now-iconic 1990 drag-ball documentary Paris Is Burning. That film we can recommend unequivocally.

And finally, the last great, unwritten story of the year. The story of modern stowaways, for us inspired by a New Yorker article on historical stowaways. Did you know that in the 1920s, in the roaring din of the Jazz Age, teenagers fueled a stowaway fad? They sought contraband adventures on the oceans, mailed themselves across the world, and altogether inspired each other by way of sensational newspaper reports in just the same way kids today might “live-stream themselves atop the roofs of tall buildings.”

So what was the current state of the stowaway, we wondered? Alas, for every story or two about a child escaping a shopping trip by sneaking his way onto a flight to Rome or an intrepid soul sailing the world undetected in the bowels of a cargo ship, there’s a dozen heartbreakingly tragic ones about freezing to death in the wheel well of an airplane or living through hell on the law and humanity-deprived high seas. Compelling, no doubt, but not stories we felt equipped to tell.

Sometimes, though, when our research takes us in a different direction than we intended, we see it through and wind up with some of our most captivating content. It happens more than you think, like when last 4th of July we decided to celebrate Independence Day by celebrating one of America’s greatest travel writers — Mark Twain. Through our research, we learned that Twain’s views on race were too problematic to be shrugged off with “it was a different time then.” Instead of shutting down the story, we presented the full picture and pivoted to an honest conversation about satire, controversy, criticism and context.

In the end, maybe we could have — or should have — forged ahead with a few of these story ideas. Who knows, maybe it would’ve led to some of our best work. Or maybe we just said all that really needs to be said (by us) on these topics. It’s hard to know for sure, but it’s something we’re always thinking about. ▪