Mark Twain wrote one of the 19th century’s most popular travel books. But the ugly ways in which he often described the world say more about him — and perhaps America — than the places he visited.

Being travel writers, we thought we could use the opportunity of July 4th to talk about America outside of its usual confines — far away from the familiar controversies and politics of the country — by writing something about the history of Americans traveling abroad. So I set out to do a little research about famous American travelers and I came across Mark Twain. I was surprised to learn that throughout his lifetime, Mark Twain’s best-selling book wasn’t The Adventures of Tom Sawyer, and it wasn’t Adventures of Huckleberry Finn.

It was his 1869 travelogue, The Innocents Abroad.

And I thought — perfect. Who better to provide observations about Americans abroad than arguably our country’s most legendary comic mind? Who’s more quintessential an American than Mark Twain?

As the tone here slides toward revelation, I’ll spoil the conclusion. The idea that Mark Twain transcends today’s controversies and politics? That was naive. Yes, I knew about the controversy surrounding the language and themes in novels like Huckleberry Finn, but in the interest in full disclosure, I thought Twain had survived those cultural battles with reputation intact. When I think of Twain, I think of the man who has his name stamped on a Kennedy Center prize for American humor. The man whose actual bust is given to the most celebrated comedians of the day, people like Will Ferrell, Tina Fey, and Dave Chappelle. I thought The Innocents Abroad would give me nothing but pithy, above-the-fray, 19th-century zingers about boorish Americans lost amidst the great world beyond the borders.

I learned my lesson: Twain does not remain above the fray.

As I dug deeper into the book, I found that some of the controversies that have always plagued America — prejudice, intolerance, racism — were inflicted too on the rest of the world by America’s most important comic writer. Even as he traveled everywhere but America, Twain packed America’s most enduring problems along for the trip.

To us, that baggage is as important to think about as anything else on July 4th, so we made the decision not to search out a new subject or tell a more flattering tale. After all, we’re only as good as our darkest moments — though, as you’ll see, there is light at the end.

A Controversial Gift for Obama

The clearest way to introduce the content of Twain’s travel tome might be to relay a recent controversy it stirred. When Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu visited President Obama in 2009, he reportedly carried with him one book to give the new president: a first edition of The Innocents Abroad. The gift was controversial for two reasons, even as reports varied as to whether Netanyahu actually handed it over:

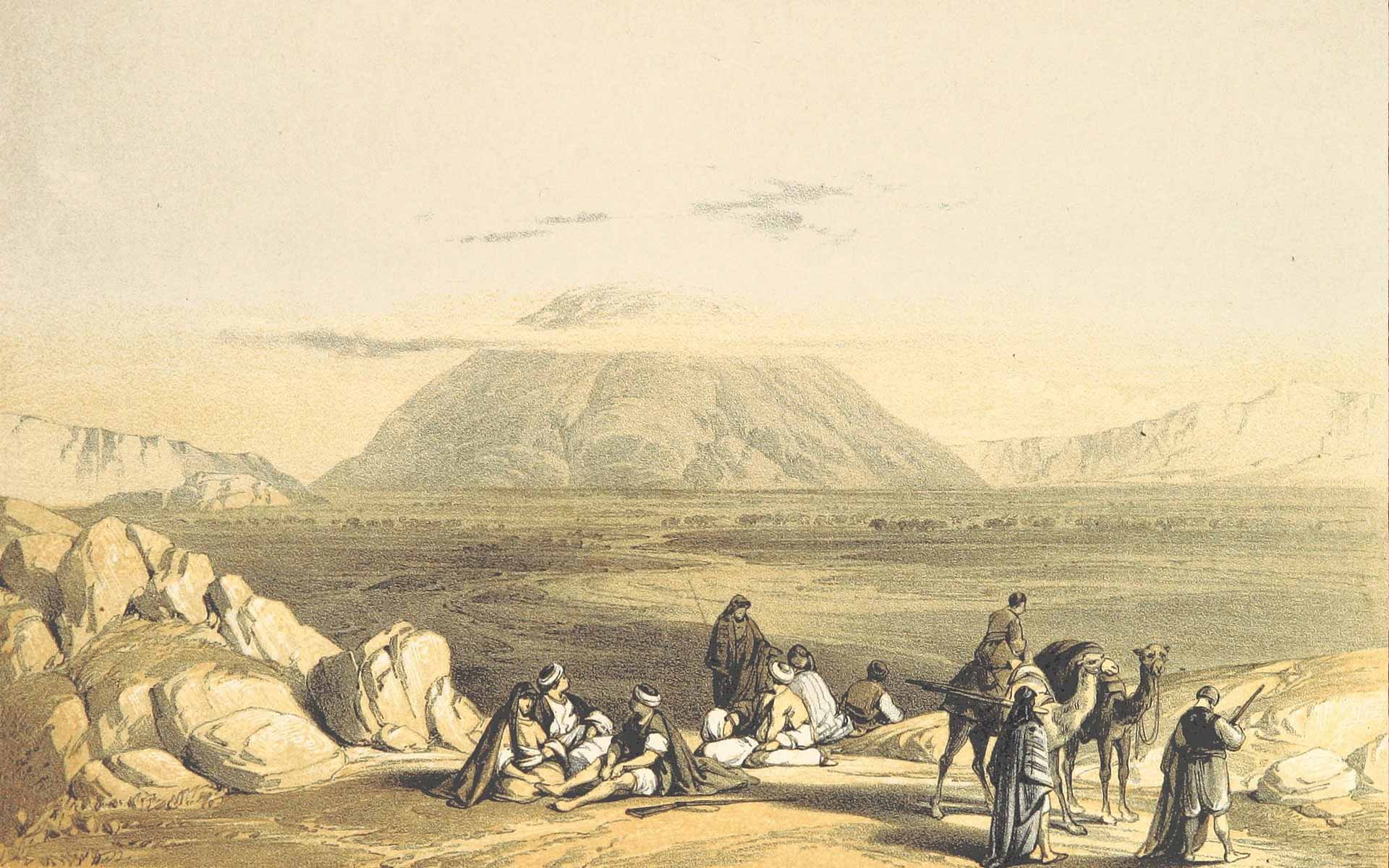

1.) As one New York Times writer explained in the midst of the controversy, passages of the book that describe swaths of desolate land in what became current-day Israel are sometimes questionably employed, including by Netanyahu, to “prove that the Arab presence… was so insignificant” that Palestinians have no claim to the land.

2.) Mark Twain’s depictions of Arabs and Islam in the book are abhorrent. At the time, one journalist cited a particular passage in which Twain describes the Ottoman Emperor as the “representative of a people by nature and training filthy, brutish, ignorant, unprogressive, [and] superstitious.” In the same passage, he calls the French Emperor the “representative of the highest modern civilization, progress, and refinement.”

How Do You Critique a Satirist?

It seems any defense of Innocents Abroad that acknowledges Twain’s prejudice ultimately brings up the same points. One is that Twain exhibited racist attitudes in the book, but he aimed his contempt in all directions. As the NY Times wrote in 2009, Twain was “equally scathing about most of the world’s people, including Americans.”

A few examples lend that argument a certain temptation. Twain calls the Portuguese “slow, poor, shiftless, sleepy, and lazy” without a second thought. He admits that a sultan’s bigamy “makes our cheeks burn with shame… in Turkey. We do not mind it so much in Salt Lake, however.”

Another defense of Twain is to say he’s just a comedian, embellishing as a rule, pledging more fealty to laughs than to truth. It’s the same argument used to defend comics judged to cross a line today — that jokes are jokes, and standards have to be different for an artist than for anybody else. As one critic put it, Twain was just “stirring these ant hills… [to] exercise his function as a journalistic humorist.”

But the truth is that as Twain travels the Middle East a more disturbing pattern emerges, one of a writer who finds redeeming qualities in some cultures he encounters and not in others.

Twain In Context

Academic Nancy Bakht has that opinion, and in an extremely compelling essay she points out many of the ways that Twain reveals a bias against Arabs and Muslims that he doesn’t show against Europeans. She admits that Twain “complains and ridicules everything along the way,” but concludes that “the change in the level of intensity and venom in his description of the Arabs and Turks is undeniable.”

She continues, arguing that his animosity is informed by a history of Western Islamophobia, and, at the time of Twain’s writing, his various barbs would play right into his American audience’s preconceived notions of a “barbaric” people in an inferior culture. In that case, a defense of Twain as “just a comedian” is untenable. To put it in context of today’s comedy, you might consider whether Twain was punching up at exalted targets or punching down at people his audience was already taught to despise.

To use a few of Bakht’s examples, when Twain says that in Turkey “the only solitary thing one does not smell when he is in the Great Bazaar, is something which smells good” or that it’s packed with “weird-looking and weirdly dressed Mohammedans,” does his audience actually interpret it as a joke? Bakht quotes one professor, Douglas Little, in making that particular point:

“To be sure, some readers of Twain’s account must have marveled at the author’s sarcastic wit, but many more probably put down Innocents Abroad with their orientalist images of a Middle East peopled by pirates, prophets, and paupers more sharply focused than ever.”

Again, would the audience of Twain’s time, unlikely to ever visit these faraway lands for themselves, take his descriptions as harmless jokes, exaggerated for effect, or as truths passed down from one of America’s most important pundits? If the current rhetorical landscape is any indication, where even today the wholesale discounting of entire peoples is still seen as effective political strategy, the latter is likely the correct answer.

Twain vs. Chappelle

There’s an interesting parallel to a modern comedian, himself controversial, who’s brought up the same questions, albeit consciously. Dave Chappelle — 2019 recipient of the Mark Twain Prize for American Humor — explained that he left his popular T.V. show for fear that his audience was laughing for the wrong reasons.

From Time Magazine, here’s an anecdote regarding the final season of Chappelle’s Show:

The third season hit a big speed bump in November 2004. He was taping a sketch about magic pixies that embody stereotypes about the races. The black pixie — played by Chappelle — wears blackface and tries to convince blacks to act in stereotypical ways. Chappelle thought the sketch was funny, the kind of thing his friends would laugh at. But at the taping, one spectator, a white man, laughed particularly loud and long. His laughter struck Chappelle as wrong, and he wondered if the new season of his show had gone from sending up stereotypes to merely reinforcing them. “When he laughed, it made me uncomfortable,” says Chappelle. “As a matter of fact, that was the last thing I shot before I told myself I gotta take f______ time out after this. Because my head almost exploded.”

Again, there’s the massive distinction here that Twain, a white man in the 19th century, didn’t concern himself with whether he was reinforcing stereotypes or not. And that he himself likely believed the worst of them right along with the public. But even if you ascribe the very best intentions to Twain, and say he mocked everyone equally in the service of comedy, Chappelle’s concerns reinforce the point of the scholars:

That’s not a good thing.

Travel Is Meaningful

One writer summed up Twain’s turn as travel writer like this: “In many ways, Twain was a bad traveler. He is cynical, arrogant and sometimes racist. The description of an unknown destination requires a stable foundation of empathy.” That Twain lacks empathy on his travels is obvious. And, being travel writers, we have to condemn the loathsome attitudes he expresses without reservation.

Empathy is the very foundation of travel, something even Twain himself seemingly comes to realize by the end of the book. In his conclusion, Twain proclaims that “travel is fatal to prejudice, bigotry, and narrow-mindedness” and admits that Americans thus “need it sorely on these accounts.” He goes on:

“Broad, wholesome, charitable views of men and things can not be acquired by vegetating in one little corner of the earth all one’s lifetime.”

It’s enough to make me nod my head before slamming it between the 700 pages of hypocrisy preceding it. It’s also a big reason why we marched forward with this story. Even amidst Twain’s seemingly proud ignorance, he aligns himself with the exact ideals that Tablet encourages: to experience cultures and customs different from your own, to travel as much as you’re able, and to discover that your comfort zone is a lot bigger than you ever imagined. We might never accept the way Twain wrote about these places, but he traveled to them nonetheless, and he came away, at the very least, a little less unfamiliar — and more than a little willing to tell others to go out and experience the world for themselves.

Regarding another Twain controversy, one professor argued in Stanford Magazine that, “Just as Huck Finn enters the classroom as a ‘classic’ but then engulfs students in debates about race, racism, religion and hypocrisy, Mark Twain enters the national consciousness as an icon and then upsets our equilibrium and complacency, pushing us to ask questions we hadn’t planned to ask.”

When we set out to write about American travelers, we certainly didn’t mean to have this conversation, but we’re glad we did. Maybe, too, that’s the best thing we can say about The Innocents Abroad. ▪